Connecting the pieces of an MF care team

Connecting the pieces of an MF care team

9

min read

Everybody’s MF is different. This story does not constitute medical advice. Please talk to your doctor about your specific case. Participants featured have received compensation as paid participants for Sobi.

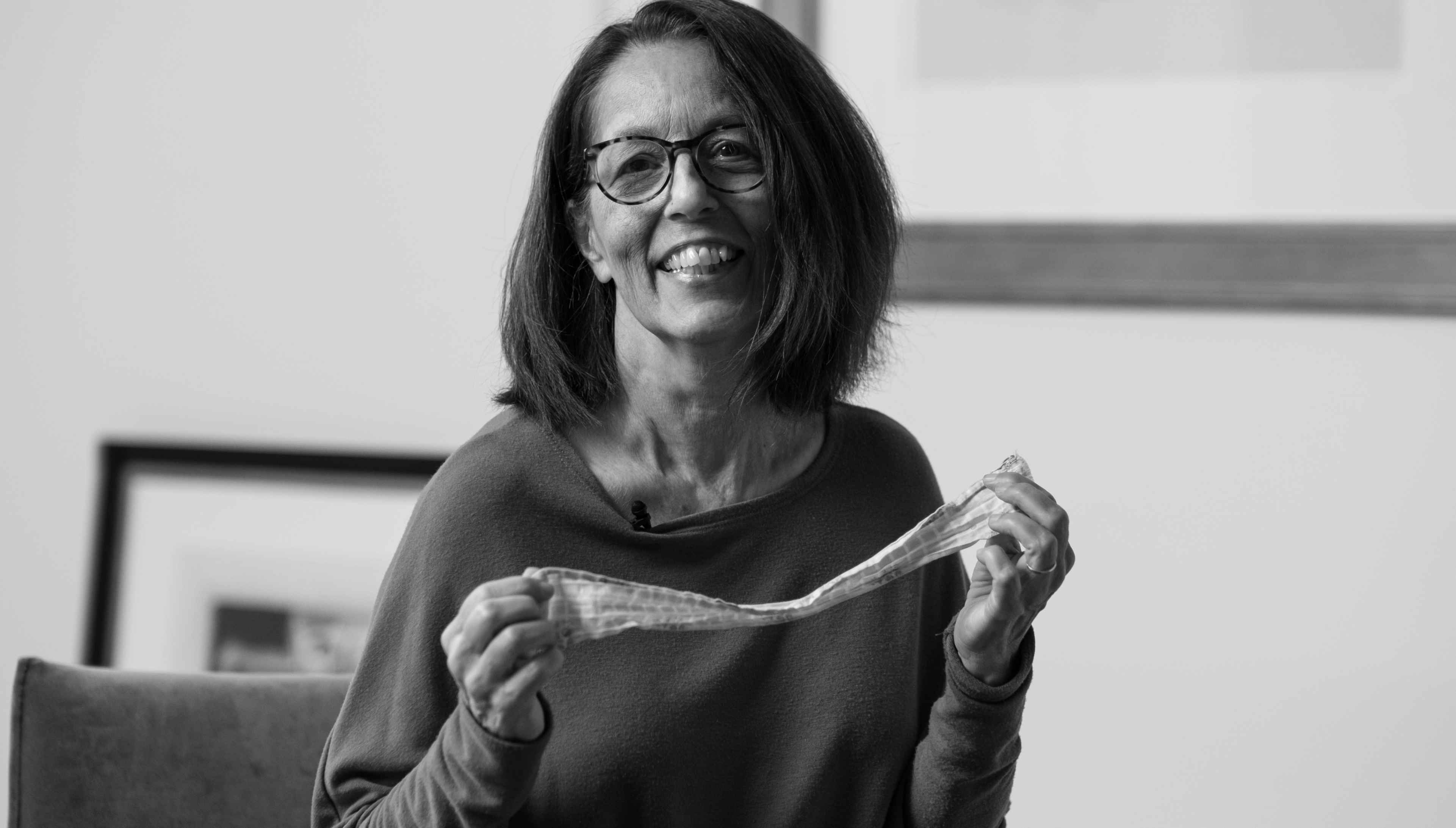

For over 40 years, Gail has taught drawing and painting classes, helping thousands of people to see and realize new possibilities.

So, it came as a shock when a doctor said there was nothing they could do to help her—they were out of possibilities.

That was 2018, when Gail’s hematologist at a nearby hospital diagnosed her with myelofibrosis (MF). “The only option they gave me was a bone marrow transplant,” she says. “Without that, they said I had 2 years to live. It was just overwhelming.”

The hematologist seemed optimistic about the transplant, even with Gail’s pre-existing condition of peripheral artery disease (PAD), so Gail began the transplant preparation with a round of pre-surgery chemotherapy. Soon thereafter, she was diagnosed with another disease— congestive heart failure. “That wiped me off the schedule for the transplant,” she said. “And they told me they had no other plans for me—there was nothing else they could do.”

Gail wouldn’t take no for an answer. “I did my research,” she says and started to learn more about MF. She Googled the disease, found organizations like Patient Power that shared valuable resources, and joined a Facebook group of patients and caregivers affected by MF. During her search, the same piece of advice kept coming up—since MF is a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) (a disease of the bone marrow), find an MPN specialist with deep experience with MF. “I didn’t even know what an MPN specialist was!” she exclaims. So, she began her search for an MPN specialist.

There was a doctor named John Mascarenhas who appeared in Patient Power videos. She looked him up and found that he practiced at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan. While Gail lived 3 hours away in northeastern Maryland, her grown daughter and son both lived in New York City at the time, so it seemed like a good place to start. Gail contacted Dr Mascarenhas’ office and booked her first appointment for New Year’s Eve 2019.

Still not a candidate for a bone marrow transplant, Gail and Dr Mascarenhas agreed that she would start a clinical trial in early 2020. Gail began taking a daily pill, and every 3 weeks, her husband and caregiver Bob would drive her 3 hours to Mount Sinai for a check-up with the clinical trial team. Given her anemia (low red blood cell count that can cause fatigue), she also needed a blood transfusion at these visits. Sometimes Gail and Bob would drive home the same day. But most times they would either stay overnight with their daughter Rachel in Brooklyn or rent a room at a guest house, paid for by the clinical trial, near the hospital.

The effort proved fruitful at first. The nagging fatigue transformed into a feeling of “euphoria,” as Gail describes it. She had more energy and felt more like herself in those first weeks. But by her next visit her platelet counts had dropped. (Platelets are blood cells that form clots to help stop bleeding.) This is called thrombocytopenia and is not uncommon with myelofibrosis. Gail had to switch to taking half a dose of her medication, and the euphoric feeling vanished.

“I was on that trial for over 2 years and nothing seemed to change. My spleen just kept getting bigger,” says Gail. “I felt OK but really didn’t have enough energy to do anything the whole time.” There was some good news. The two colleges where she taught art and design classes allowed her to move to online work even before COVID started. So, she was able to customize her workday around her fatigue and rest when she needed to.

After 2 years, though, Gail was looking for more. She and Dr. Mascarenhas discussed the possibility of switching to another clinical trial, this time with a more intensive treatment. “I knew the medication was more toxic, but I was really looking forward to my spleen getting smaller,” says Gail. She participated in this second trial for a few months during the summer of 2022. Gail had constant diarrhea and ended up getting colitis, an inflammatory disease of the colon; her blood counts also started dropping again. It was time to stop the treatment.

In December 2022, Gail was just starting her third clinical trial for MF. She’s hopeful that a new drug might give her some relief.

A year before being diagnosed with MF, PAD, and congestive heart failure, Gail began to feel moments of overwhelm. “There was a time when I could hardly move. Weird things were happening to me, and we didn’t know why,” she explains. “I was just so stressed out.” What used to be everyday activities for her, like going to a department store, started to make her hyperventilate. “The bright lights and activity were too much for my system,” she says. This is when her symptoms started keeping her closer to home, and the feeling of deep isolation crept in.

Now several years later, Gail still struggles with fatigue. “It’s unlike anything I could ever describe,” she says. Her blood counts are low enough that she needs a blood transfusion every 2 weeks instead of every 3 weeks. “If it were up to my body, I would just keep sleeping. It’s nothing to sleep for 12 hours,” she says.

While she gives her body time to rest, Gail does try to keep up with some daily activities as much as she can. “I never know how I’m going to feel. Most days, I grade for a few hours in the morning and early afternoon, and like around 3 o’clock in the afternoon, I’m finished.” By 7pm, Gail is usually in her bed for the evening. This routine works for her, she says, “It’s comfortable.” On good days, she may have enough energy to meet a friend for lunch, straighten up the house a bit, or make dinner. But she still feels nervous about leaving home. “Like during COVID when everyone had to stay put, it was weird to go out. This is the same thing.”

Being in public also makes her feel self-conscious about her appearance—she has an enlarged spleen and liver and has extra fluid in her abdomen. “When I was first diagnosed, I saw this picture of a woman on the internet, completely nude, skinny as anything, with this gigantic stomach, and I’m like ‘Oh my land!’ And that’s exactly what I look like now,” says Gail.

She does her best to feel good about going out. “I found this sweater in my closet that I haven’t worn in a really long time that is nice and big, and I’m going to wear that on Sunday when I meet friends for brunch,” she says. She hardly ever gets dressed up anymore, so she decided to practice getting ready a few days before, putting on her outfit and doing her hair with a cute headband that her son bought her. “It makes me feel better about going on Sunday,” she explains.

Through all the uncertainty that MF brings, Gail has found some tools that help her cope. One of those tools is keeping weekly appointments with a trusted therapist. “My therapist is really helpful and keeps my head straight,” says Gail. With her therapist’s guidance, Gail has become more comfortable with not being as active as she used to be. “She helps me think, ‘It’s OK. This is where you are right now. You can’t do a whole lot; don’t beat yourself up over it,’” says Gail. “She reminds me that I’m taking good care of myself.”

Another way that Gail feels more grounded is by practicing light yoga poses. Moving her body slowly and gently at home works for her because it is much more manageable energy-wise than other types of exercise, like walking. “I just don’t have the damn energy!” she exclaims.

And then there’s her art. Throughout her journey, Gail’s love for the arts has never faltered. She needed to pivot what she does, but she found ways to stay connected. Once a children’s book illustrator and painter of portraits and still lifes, Gail is able to continue online teaching in art and design, which she started when she was diagnosed.

“I love interacting with my students,” Gail said. “It keeps me current. I love learning new things I can teach them. All of this done from the comfort of my favorite spot on the couch.” And although not as prolific as she once was, she tries to paint once a week.

“My therapist encouraged me to make it a weekly thing to get back into my art,” says Gail, so she started exploring digital drawing. Lately, “I’ve been painting still lifes,” she said. Most recently: persimmons. Getting back into creating again was “really rewarding,” she added.

Gail says she is a naturally optimistic person, but 2023 presented new challenges. She is scheduled for surgery to remove plaque in her arteries, and she’s starting a new clinical trial. “After a while, you’re like, ‘How much more of this can I take?’ It starts to get old, you know?” Gail admits to feeling depressed and having a hard time waking up in the morning. “I got this gray cloud over me,” she says, “and it takes me some time to start to feel better.” She realizes, as she says it, that she hasn’t told her care team about her depression yet. “I gotta tell them during my next visit,” she says.

That seems to be Gail’s strength—facing what comes, talking about the obstacles with her MPN team, and turning to her village for care and support. “All of this, everything that I’m going through is everything that everybody goes through in all kinds of trials and tribulations in life. I try to breathe deeply and try to be positive in my mind. I try to continue being good to myself and taking care of myself. I really wanna get better.”

For patients newly diagnosed or struggling with MF, Gail offers some advice: